German Submarine U-505

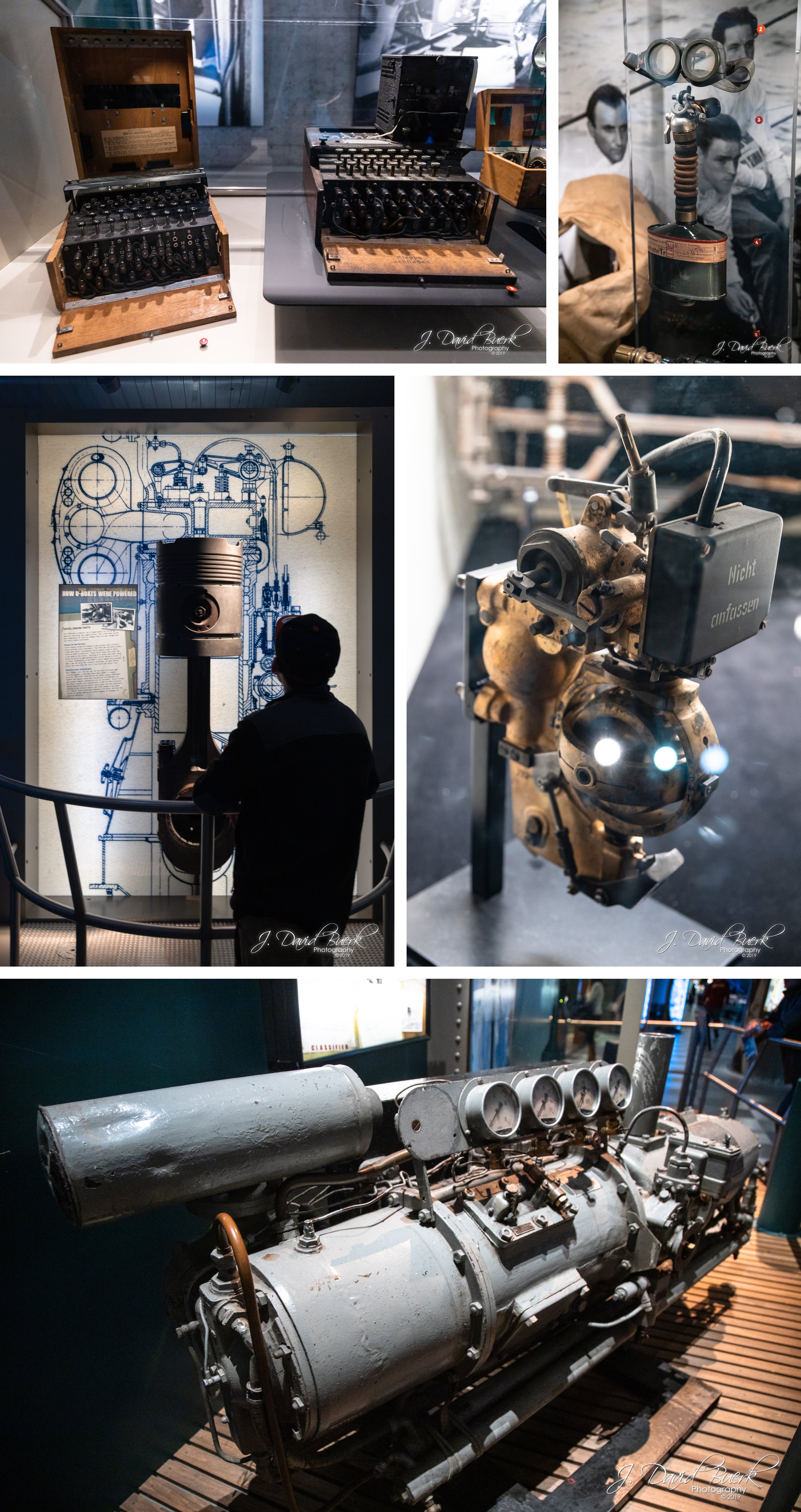

One of my favorite movies is U-571, which tells the tale of an American submarine capturing a stranded German U-boat to obtain its onboard Enigma code machine. This Matthew McConaughey film is extremely fictionalized, and in fact the real U-571 was never captured; it was sunk via depth charging by the RAAF off the coast of Ireland. During the course of WWII, approximately 15 Enigma machine or Enigma codebook captures were made by the Allied Forces, only one of which was by US forces. In June, 1944, the US Navy captured the U-505, which provided much of the premise for U-571. However, unlike the film heavily implied, it was actually British forces that captured the first Enigma, three years prior when HMS Bulldog captured U-110 on May 9th, 1941. U-571 presents an amalgamated plot of the captures of U-110 and U-505. Although U-505 was not used in filming U-571, film crews reportedly visited and extensively studied the submarine to partially recreate parts of it for the film.

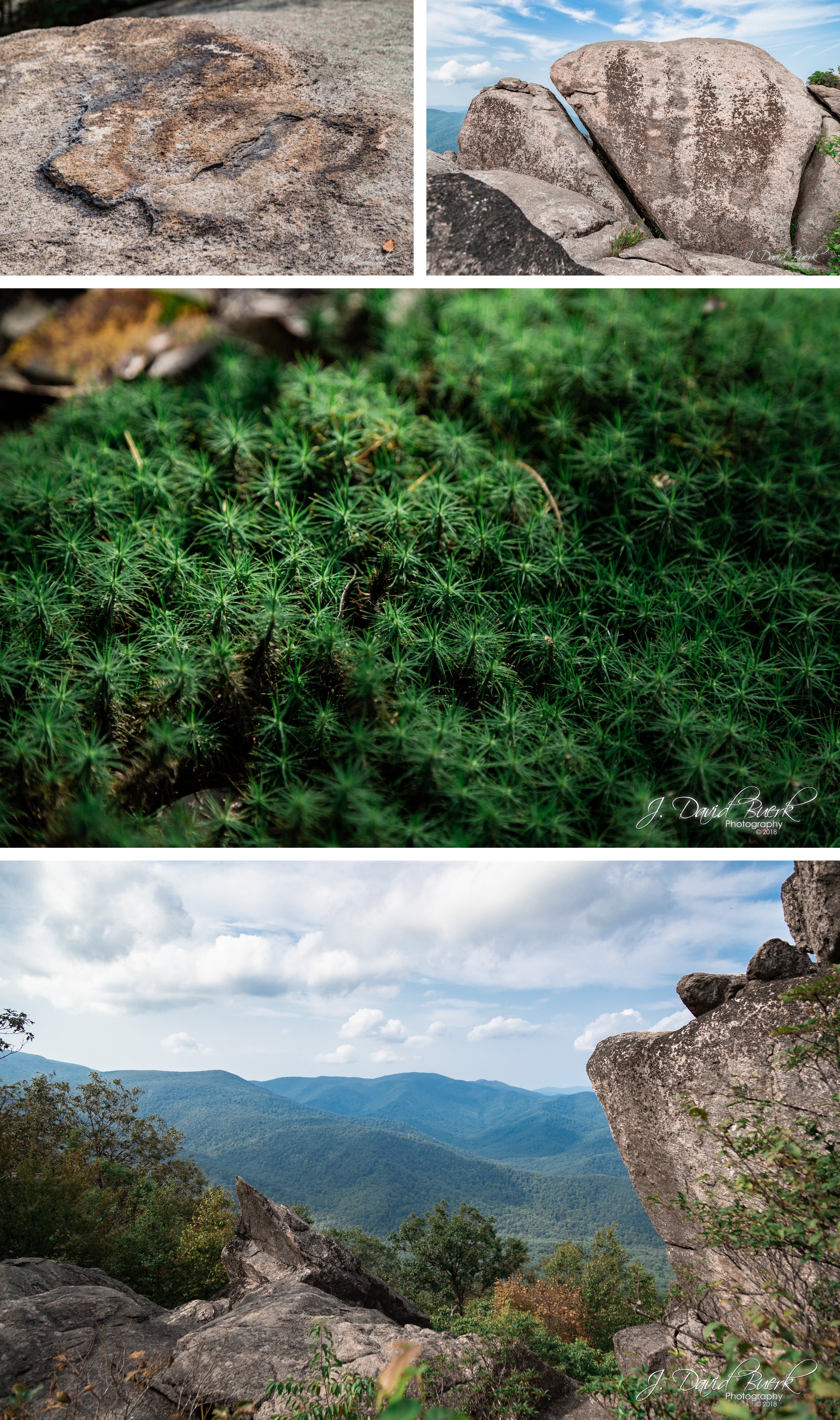

In reality, the U-505 sunk 8 ships over the course of its 12 patrols and two year service history. The US Navy launched a six ship Task Group to hunt U-505 when British Ultra intelligence intercepted generalized locations of German U-boats off the coast of Spain. The Task Group, consisting of one aircraft carrier and five destroyers, made sonar contact with the U-505 on June 4th, 1944, shortly after Captain Daniel V. Gallery had called off the search as the Task Group had exhausted their fuel. With air support from aircraft carrier Guadalcanal, destroyer Chatelain dropped depth charges that crippled the U-505, forcing it to surface. Oberleutnant zur See (Lieutenant) Harald Lange ordered his crew to abandon ship and scuttle the boat, but the 59 man crew could not disembark before the nine member US boarding party was able to board the U-505, close the valves filling the submarine with seawater, and disarm scuttling charges set by the German submariners.

All but one of the U-505’s 59 man crew survived the Allied assault and capture, and only three other crew members were injured. The crew was ferried to Bermuda aboard the Guadalcanal, before being transferred to a POW camp in Ruston, Louisiana several weeks later. To maintain OPSEC and the illusion to Germany that the U-505 had been sunk with no survivors, the POWs were kept separately from others in the prisoner population, and all letters or attempts to communicate outside the camp were confiscated; a direct violation of the Geneva Convention. The imprisoned crew members even constructed makeshift balloons out of cellophane and hydrogen yielded from mixing cleaning chemicals in order to convey their letters over the camp walls with the hope residents of the nearby town would find them and forward the messages to their family, but these attempts were unsuccessful. Some of the POWs learned and played baseball with members of the US Navy baseball team who were tasked as guards at Camp Ruston. Upon the end of the war in 1945, the interned crew began being returned to Germany, with the last remaining captives repatriated in 1947.

As for the U-505, the United States and Allied forces had to hide the submarine to maintain the illusion to the Axis powers that they had captured the missing boat and the valuable Enigma ciphers and codebooks it carried. The U-boat was ferried to a naval base in Bermuda to be studied by US intelligence and naval engineers. To further hide the captured German U-boat, the U-505 was painted to resemble a US submarine, and renamed the USS Nemo. By 1946, US intelligence had gathered all useful information from the U-boat, and dismantled most of the ship’s interior. Having no more use for the ship, the Navy planned on using the U-505 for target practice until it sank. Rear Admiral Daniel V. Gallery got wind of the plan, and through his brother connected the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry with the Navy to form a plan to donate the U-505 to the newly formed museum, which was already planning on acquiring a submarine to exhibit. On September 25th, 1954 the U-505 was dedicated was dedicated as a permanent exhibit, and a war memorial to all sailors whose lives were lost in the first and second Battles of the Atlantic. In 2004, due to over 50 years being stored outdoors, the U-505 showed heavy wear from the elements, and was subsequently restored and moved to a newly built permanent dry dock inside the Museum of Science and Industry’s East wing.